Life inside the Pontifical College Josephinum is structured in solemn study punctuated by prayer (and an occasional beer)

This article is part of a weeklong series

"Answering the Call" which includes daily articles and slideshows.

By Todd Jones

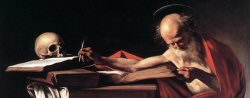

Photo at left: Deacon Robert Bolding, left, gives the kiss of peace to new deacon David P. Miller during an ordination ceremony for deacons in April. Photo by Fred Squillante

Traffic snaked along N. High Street near I-270 in a bumper-to-bumper line of frustration as the sun rose over the Pontifical College Josephinum.

The taillight-flashing bustle of commuters contrasted with the serenity a few hundred yards away, where students flowed quietly into a chapel inside the seminary's College of Liberal Arts building.

Some carried Bibles, others small prayer books. Each was bleary-eyed and silent.

The mid-February morning was like every morning for those men studying to be Roman Catholic priests at the Vatican-owned school on the Far North Side.

The students were gathering for the 7:30 a.m. recitation of the Liturgy of the Hours, a quick prayer they also gather to say in the evening -- and offer in private three other times each day.

"It sets a rhythm to your day," said Deacon Robert Bolding, a fourth-year theologian assigned this day to lead the undergraduates in prayer. "It sanctifies time."

To help replenish its thinning ranks, the Catholic Church needs men willing to dedicate nearly a decade to priestly training that is disciplined, demanding and, Robert said, as slow as a stalactite's growth.

"That's one of the great challenges," said the Rev. Jeff Coning, vocations director for the Diocese of Columbus. "That's eight years that you need a student to sit there and work, and kids today are used to living life by a Palm Pilot. "

Seminarians say the adjustment doesn't come easy, and even those close to becoming priests struggle at times with the rigid structure.

"It's like a real long boot camp," said Robert, a Phoenix native. "Sometimes, I feel choked by the whole routine of it."

His routine has been basically the same -- prayer, Mass, classes, homework -- since he entered the St. John Vianney College Seminary in St. Paul, Minn., eight years ago, and enrolled in the Josephinum's School of Theology in 2005.

To describe seminary life, he uses the analogy of a tree being surrounded by other trees: it only has one place to grow, and that's up.

"It helps discipline your soul and helps us grow to God," Robert said. "That's the value of formation and living accordingly to the external rules. That's part of what makes you a priest. That's part of learning obedience and self-sacrifice. But it gets old."

Robert, 27, lived his final seminary year alone in an undecorated room without a TV or stereo (although Josephinum rules permit both) in a dorm hall with a community bathroom.

He owned few clothes other than his black clerical garb. He drove his parents' car because he has never owned one.

"Somebody sets my schedule," said Robert, bound by the Josephinum's curfew of 11 p.m. weeknights and midnight on weekends. "If I miss something, I have to have an excuse. It's understandable why it has to be like that in the seminary, but I'm approaching 30."

Still, Robert considered seminary life to be a great blessing, enabling him time to concentrate on studying and discerning God's call.

Each Josephinum student is assigned a Director of Spiritual Formation from the faculty to help guide him through the four pillars of formation -- spiritual, intellectual, pastoral and human -- directed by the Vatican and U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

"You spend hours in prayer to give your will over to God: Is this what you want for me?" Robert said.

Mystery is part of that divine process and also part of this place.

The Josephinum's bell tower rises nearly 200 feet and was the highest point above sea level in Franklin County until the Rhodes Tower was built Downtown in the 1970s.

Every day, thousands of commuters drive by the brick and limestone tower along N. High Street, yet few have stepped inside the Gothic-style administration building or seen its 900 windows, the terrazzo floors or the inlaid wood paneling.

"I think the Josephinum is like the Wonka Factory of Columbus," said third-year theologian John Eckert. "Everybody knows it's there, and they've seen it, but they have no idea what goes on behind the gates."

Seminarians who venture off their private campus, 11 miles north of downtown Columbus, hear their home described by outsiders as the castle in Harry Potter movies.

The Josephinum sits on 75 pastoral acres, with manicured fields (including a cemetery) and a front driveway lined with trees. The collection of four buildings houses dormitories and four chapels.

A curious Ohio family once stopped by the school -- the only pontifical seminary outside Italy -- and visited with its rector and president at the time, Monsignor Paul Langsfeld.

"They thought it was a monastery where we milk cows, make our own bread and make curd," said Langsfield, who left the school in July for a new assignment.

With the Catholic Church need- ing more priests, the Diocese of Columbus' vocations director often finds himself addressing misconceptions about seminary life.

"Parents want to know: How often am I going to see my kids?" Coning said. "The big concern of (candidates) is: Are they going to be able to socialize and have friends like they would at other places?"

Josephinum students discover that they have time for social and athletic recreation. The school offers intramural sports and hosts a basketball tournament each February for visiting seminary teams.

J.J.'s Pub, the campus bar in the basement of the theology building, has a flat-screen TV and is home to karaoke, the "Pub Olympics," trivia nights, Mardi Gras and Super Bowl parties, and fantasy football league arguments.

"Guys have fun," said Deacon Michael Ross, the Josephinum's academic dean. "They like their rock 'n' roll. They're not walking around here uptight and never smiling. They're young American guys. It's not monks. It's not prison."

Demands were different when Monsignor John Joseph Jessing, a German immigrant, founded the Josephinum in 1888 at 17th and Main streets, near Downtown. (The school moved to the Far North Side campus in 1931.)

Before the Vatican II conference, during which bishops made liberal changes to church doctrine and practices in the mid-1960s, the Josephinum was more rigid. Students spoke only German in the first half of each month. Their mail was censored. A priest chaperoned them off campus.

"Those days are long since gone," Ross said.

To get out that message, the Josephinum, which had a high school until 1967, conducts campus tours. Students' families are invited to spend a weekend at the seminary each fall, and the public is welcome at the school's annual Irish Festival in February.

"It's good for people to interact with vocations and see that priests just don't fall out of the sky," Robert said.

The call to priesthood is more mysterious than momentous.

"It's the still, small voice -- an idea you can't get out of your head," Robert said. "It's something you're drawn toward."

Although the seminary helps with discernment, doubt still creeps in.

"You're never certain you can do it," Robert said. "I know being this close (to ordination), I could not do what a priest needs to do without the grace of God."

Robert was reminded of that in late February when he assisted in a Mass attended by 68 Josephinum undergraduates, most of them barely removed from high school.

Some were nearly a decade younger than Robert, and many won't become priests.

Langsfeld said the Josephinum sees up to 20 percent of its undergrads drop out each school year.

"It's normal for a collegian to come and realize over a certain part of time that this is not for him," Langsfeld said. "We've had guys come, leave, and come back after several years."

Robert did so. Three semesters shy of his undergraduate degree, he withdrew from St. John Vianney College Seminary.

He was 21, struggling with faith issues and "just not feeling it."

"I didn't have the maturity then to stick it out with the ups and downs of the seminary," he said.

Robert stayed in St. Paul, moved into an off-campus apartment, took a catering job and continued school as a nonseminarian at the University of St. Thomas.

His parents, Patty and Al Bolding, never questioned their son's decision.

"We just supported him," said his mother. "We told him, 'Robert, you've got to follow your heart and listen to what God is telling you.'"

Free from the seminary, Robert dated a woman for six months, but the relationship ended. He traveled to Rome and felt stirred to return to the seminary.

When he returned to Minnesota to finish school, he met an attractive woman.

"It was a platonic relationship, but I really loved this girl, and she reciprocated that love," Robert said.

That love, however, couldn't eclipse his heart's calling. Robert decided to re-enter the seminary and was accepted back by the Diocese of Phoenix, which sent him to the Josephinum in 2005.

"Anytime I have a moment of second-guessing, I always have that to rely on: I loved somebody, she loved me, and I still knew I was called to the priesthood," he said.

Now, four months shy of the priesthood, Robert gave the Mass homily to undergraduates who face their own questions about the future.

"Jesus says, 'If you want to follow me, you have to take up the cross and come after me,' " Robert preached. "If you want to live, you have to throw your life away. That tells us the Christian life is about death."

He understands now that the seminary is a place you go to die -- to give up your secular desires and rise to God's wishes.

Homily complete, Robert sat down in the silent chapel.

A priest stood up.

"For an increase to the priesthood and the religious life, we pray to the Lord," he said.

The young seminarians answered in unison:

"Lord, hear our prayer."