From the National Post

From the National PostBy Fr. Raymond J de Souza

Childlessness advocates tell us, in sum, that children require a lot of sacrifices. That's not news. What may be new is that people now feel confident enough to argue publicly that those sacrifices are too great -- in short, that the child is not worth it. I say "may be" new because while the technology has changed over the millennia, the human heart has not. No doubt in every age there were a few who thought children not worth the bother.

The book excerpted in these pages this week makes the argument that life would be more convenient, and therefore happier, without children. That does not really follow. Many things, including most things that give meaning to life, are inconvenient on one level or another. A life of great ease and convenience and even wealth is not necessarily a happy one. Surely the mother at home with toddlers is more constrained than the jet-setting sybarite, but if you know people in both categories, you know that the latter is not necessarily happier than the former.

But any father or mother could tell you that. I, as you would correctly intuit, have no children. Catholic priests of the Latin rite are celibate (the Catholic eastern rites have married clergy).

Understanding the celibacy of the priest requires an understanding of what marriage and children are all about. If they were bad things, or wicked things, or merely things constraining human flourishing, then celibacy would simply be required for everybody. Only if they are good things, very good things, does it make sense to sacrifice them for something greater. So if children are such a good thing, why does the Catholic priest remain celibate?

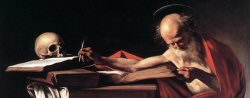

The first answer is that is how Jesus lived. He chose not to marry and have children, contrary to the norms of his time--and our time too. In the Catholic sacramental world, the priest acts not merely as a representative of Christ, but in the person of Christ Himself. What a priest does no merely human power can do--baptize, forgive sins, consecrate the holy Eucharist. So when the priest acts in the sacraments, it is Christ who acts. The priest then is meant to be an icon of Christ. That is understood, incidentally, even by those who are not Catholic, which is why priestly wickedness occasions so much attention and legitimate opprobrium.

The identification of the priest with Jesus Christ is deeply rooted in the apostolic tradition. Though the apostles were certainly drawn from married men, the biblical witness indicates that they left married life behind, or never married, in response to their vocation. The apostolic tradition has roots even farther back, in the priests of the Jewish covenant, who refrained from conjugal life when engaged in their sacred duties.

There is another dimension at work -- what we call the eschatological dimension. The priest lives now as we all hope to live one day, in the blessedness of heaven. In heaven, there is no marrying or giving in marriage, as Jesus teaches. Marriage and family are for this world. To be sure, it is precisely through marriage and family that most learn the virtues that prepare them for blessedness in heaven. But it remains a preparation.

The priest, and others in consecrated celibacy, lives now as a sign of the world to come, with his life fixed upon the promise of the eternal fulfillment God provides. In freely renouncing the great good of married life and children, the priest points to the world to come. Indeed, without the world to come, the celibacy of the priest would make little sense.

The childless by choice are aiming to maximize some of this world's goods -- education, professional advancement, travel, wealth and, to be blunt, consequence-free sex. For this they are willing to sacrifice their most enduring stake in this world: The only enduring thing we leave in this world is our children. The priest's motivation could hardly be more different. He sacrifices his enduring stake in this world not for more of this world's transitory goods, but for those things that are more enduring than this world itself.

The child by his very nature points to the future. The childless advocates reject the future in favour of the present. The celibate priest points to the future beyond the future even children promise-- eternity.

The book excerpted in these pages this week makes the argument that life would be more convenient, and therefore happier, without children. That does not really follow. Many things, including most things that give meaning to life, are inconvenient on one level or another. A life of great ease and convenience and even wealth is not necessarily a happy one. Surely the mother at home with toddlers is more constrained than the jet-setting sybarite, but if you know people in both categories, you know that the latter is not necessarily happier than the former.

But any father or mother could tell you that. I, as you would correctly intuit, have no children. Catholic priests of the Latin rite are celibate (the Catholic eastern rites have married clergy).

Understanding the celibacy of the priest requires an understanding of what marriage and children are all about. If they were bad things, or wicked things, or merely things constraining human flourishing, then celibacy would simply be required for everybody. Only if they are good things, very good things, does it make sense to sacrifice them for something greater. So if children are such a good thing, why does the Catholic priest remain celibate?

The first answer is that is how Jesus lived. He chose not to marry and have children, contrary to the norms of his time--and our time too. In the Catholic sacramental world, the priest acts not merely as a representative of Christ, but in the person of Christ Himself. What a priest does no merely human power can do--baptize, forgive sins, consecrate the holy Eucharist. So when the priest acts in the sacraments, it is Christ who acts. The priest then is meant to be an icon of Christ. That is understood, incidentally, even by those who are not Catholic, which is why priestly wickedness occasions so much attention and legitimate opprobrium.

The identification of the priest with Jesus Christ is deeply rooted in the apostolic tradition. Though the apostles were certainly drawn from married men, the biblical witness indicates that they left married life behind, or never married, in response to their vocation. The apostolic tradition has roots even farther back, in the priests of the Jewish covenant, who refrained from conjugal life when engaged in their sacred duties.

There is another dimension at work -- what we call the eschatological dimension. The priest lives now as we all hope to live one day, in the blessedness of heaven. In heaven, there is no marrying or giving in marriage, as Jesus teaches. Marriage and family are for this world. To be sure, it is precisely through marriage and family that most learn the virtues that prepare them for blessedness in heaven. But it remains a preparation.

The priest, and others in consecrated celibacy, lives now as a sign of the world to come, with his life fixed upon the promise of the eternal fulfillment God provides. In freely renouncing the great good of married life and children, the priest points to the world to come. Indeed, without the world to come, the celibacy of the priest would make little sense.

The childless by choice are aiming to maximize some of this world's goods -- education, professional advancement, travel, wealth and, to be blunt, consequence-free sex. For this they are willing to sacrifice their most enduring stake in this world: The only enduring thing we leave in this world is our children. The priest's motivation could hardly be more different. He sacrifices his enduring stake in this world not for more of this world's transitory goods, but for those things that are more enduring than this world itself.

The child by his very nature points to the future. The childless advocates reject the future in favour of the present. The celibate priest points to the future beyond the future even children promise-- eternity.

No comments:

Post a Comment